Understanding emotions may seem easy, but there is more than meets the eye to how they work, and how we can use them. As we know from the previous post, emotions serve to protect and aid us. However, in certain situations our emotional expressions may not be required, are inappropriate, or irrational for the situation at hand, and may even cause irreversible consequences.

So how do we get rid of these untimely emotions? By disengaging our triggers and desensitizing ourselves. This is easier said than done though. When we know what happens inside our bodies before we are triggered, we can know the most effective methods to disengage the trigger and keep control. If you are tired of not knowing why emotions lead you to say, act, or feel a certain way, then this article is for you.

Denying Is Delaying

First, a little insight into why denying the problem doesn’t work. Maybe you’ve tried to sweep your feelings under the rug by distracting yourself, by watching a series, taking a nap, or even a trip. Although, more often than not, when you get back to reality you’ll find that the same feelings arise when you think of, or are presented with that situation. Long story short, denial is just procrastinating the work you know needs to happen. Think about it this way, if denying had worked then why are you reading this article? So if you can’t go around it then let’s go through it.

The Shortcut

Emotions start with the perception of a situation, our experience of that event if you will. An experience is made up of sensory information, for instance, what you see, hear, smell, taste, and touch. In order to create a response to a perceived experience, our brain weighs it against previous experiences (Luck, 2014). These previous experiences are grouped together in schemas (Roediger, 2006). Schemas are our brain’s way of making a quick call to action. Because sometimes a second can be the difference between a good or bad outcome.

Today dangers may be a little less obvious, think of social interactions. For example, relationship problems because you’re afraid to trust? maybe your significant other was planning a surprise for you when instead, you thought they were hiding something bad from you. It is not like our significant other intended to trigger our insecurity and send us on a subconscious vacation to the inner Pandora’s box we didn’t even know we had. No, yet schemas still act as this shortcut. And before you know it, your body is responding by increasing your blood flow making your heart beat faster and sweat more in anticipation of the worst, which is frustrating.

The Science Behind It

So, the emotions we feel are due to our bodies assigning the situation at hand to schemas, but how does this happen?

Alright, let’s go back to high school for a moment, no, don’t worry this time without the pimples, impeccable fashion, or braces (speaking from experience).

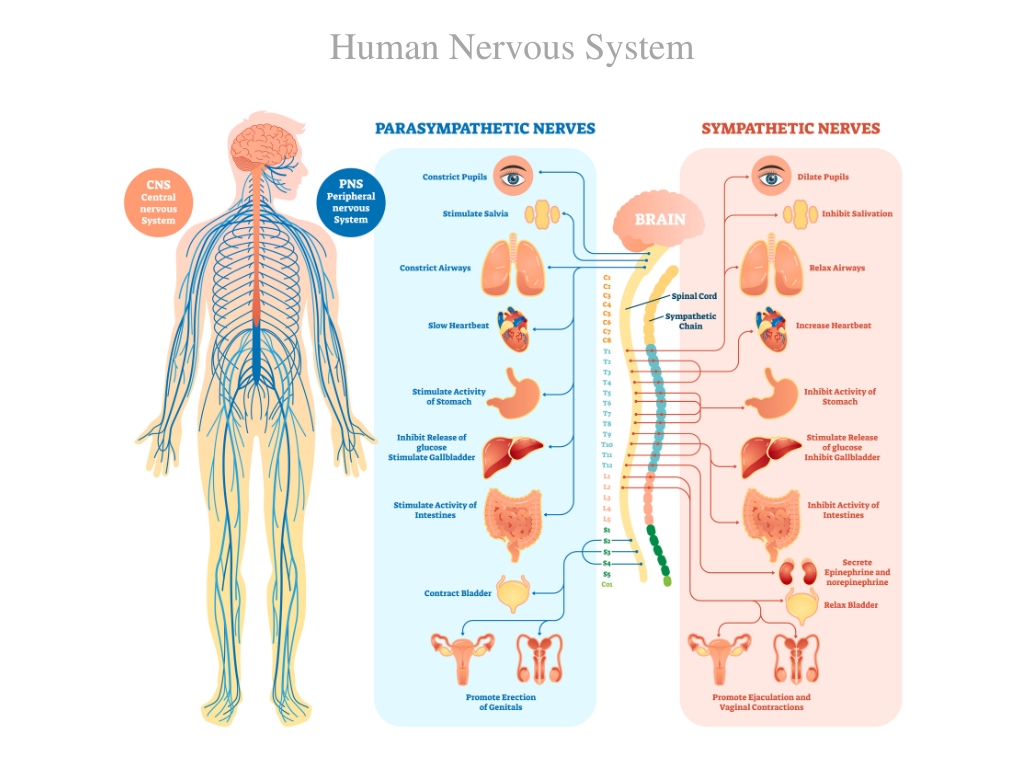

Let’s dive into biology for a minute. You might remember the central nervous system, which includes the brain and spinal cord (see left part of the image above). Then there is the peripheral nervous system which is made up of the nerves connecting your spine to your organs. The Peripheral nervous system is like a neuron highway for electromagnetic brain waves, simply put, signals. Some of these signals are voluntary, and fall under the Somatic Nervous System, like when you’re grabbing an object and you consciously reach for it. Other signals are given involuntarily in the Anatomic Nervous System, like telling your heart to keep beating and your lungs to keep breathing, (Waxenbaum et al, 2019) (Mashour, 2019) a literal lifesaver for the forgetful ones among us.

The Built-In-Guardian

In order to find where these emotions come from, we have to understand the Anatomic Nervous System better. This system is designed to take action instantaneously on the basis of sensory input in order to keep you alive. There are two parts of this subconscious built-in guardian, the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems (see right part of the image above).

To cut down on the caffeine needed we will summarise these quickly.

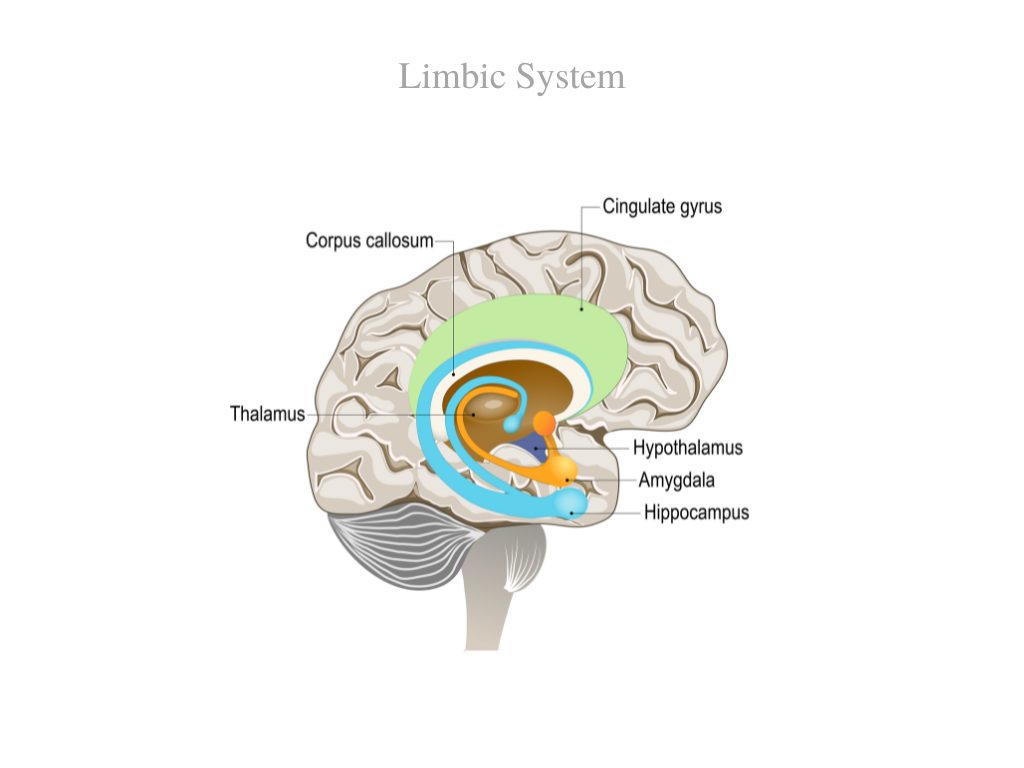

Emotional reactions start as sensory information that is organized in schemas. Based on these schemas (patterns detected from previous experiences) your brain tries to predict the best way forward in your current situation. Signals are then made in the amygdala. Signals from the amygdala are then sent to the hypothalamus in what is known as the limbic system (See image above). This is where it’s decided if the situation requires a sympathetic or parasympathetic response. Then the signals are directed to the organs responsible for the hormones that your body thinks are required to respond (Hiller-Sturmhöfel et al, 1998).

If hormones such as endorphins are released into the bloodstream, they cause a rest-and-digest state (parasympathetic nervous system). Hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline, are released in a similar matter and produce so-called negative emotions like fear or anger, and switch on the fight-or-flight response (sympathetic nervous system)(Waxenbaum et al, 2019).

So now that we know hormones are released based on which schema our brain decides the situation best fits into. We should take a closer look at hormones to understand their role in the process.

Life Through Colored Glasses

Hormones are like a pair of colored glasses. (Izard, 1999) Depending on the hormone that is released we see things in different colors. Although this may make hormones seem pretty simple, like when something is aggravating, your body releases adrenaline, and when something is pleasant, you are experiencing the release of dopamine, in truth hormones are more complex.

We don’t just simply feel one hormone at a time, rather, we get infused with a cocktail of different hormones all the time to regulate our bodily functions and determine our responses. The quantities of each hormone released are different depending on the situation we perceive.

Lastly, and arguably most importantly, hormones are also released without external stimulus. For instance when we recall a great memory from the past or when we panic about the future. The fact that we still have responses to past or future events, even if our current environment didn’t ask for a reaction, means this supposed sensory information is sent in response to thoughts that we have. (Barrett, 2017)

The Good News

Having negative or positive hormones released, without an external situation, may not sound like good news. There is a catch however, if we are the ones subconsciously controlling how we feel through our thoughts, we can take back control of our feelings by reframing our thoughts. In the next article: Controlling Emotions, we will show you how reframing your thoughts and understanding your body’s parasympathetic nervous system can help disrupt the endless negative feedback loop using science-based physiological techniques so we can alter our thoughts.

The Takeaway

Okay, that was a lot of information. To recap, we know that emotions start as sensory information. Those sensory signals (electromagnetic brain waves) then get put into schemas by your amygdala and hypothalamus. After they decide what response is needed, parasympathetic or sympathetic, the signals travel down your nervous system to your organs. Those organs then release the required hormones preparing you to act on the situation.

We also know that we get our sensory information from our perceived surroundings, whether real or not, it means that if we change our perception we should be able to desensitize our triggers. But, most of our triggers are in our subconscious minds. Therefore, to change our responses we have to bring the subconscious triggers to the conscious mind. In order to pull off this magic trick, we should try and find the root of our triggers and learn how to engage the parasympathetic response to calm down. So, if you are ready to find out exactly how to tackle those triggers through scientifically proven methods then head over to the next article on controlling emotions.

Related Articles

References:

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How Emotions Are Made: The secret life of the brain. Retrieved November 12, 2021, from https://books.google.ae/books?hl=en&lr=&id=hN8MBgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=the brain and emotions&ots=fc6QqPtD3g&sig=AST9BzJVvPcvn0lBBG5VXf8tv8A&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=the brain and emotions&f=false

Clayton, N. S., Bussey, T. J., & Dickinson, A. (2003). Can animals recall the past and plan for the future? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4(8), 685-691. doi:10.1038/nrn1180

Hiller-Sturmhöfel, S., & Bartke, A. (1998) The Endocrine System: an Overview. Retrieved November 11, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6761896/

Izard, C. E. (1999). The Psychology of Emotions. Retrieved November 11, 2021, from https://books.google.ae/books?id=RPv-shA_sxMC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Luck, M. (2014). Hormones: A very short introduction. Retrieved November 9, 2021, from https://books.google.ae/books?hl=en&lr=&id=zrqXAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=where do hormones come from&ots=vBnJ_sSvms&sig=tRD-a39N3QpjCvrLNDVXLYCvaok&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=where do hormones come from&f=false

Mashour, G. A. (2019). Oxford textbook of neuroscience and anaesthesiology. Retrieved November 9, 2021, from https://books.google.ae/books?hl=en&lr=&id=kSCDDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT157&dq=activate the parasympathetic nervous system&ots=_U6c-CPGrx&sig=AHDX4cFvNbtsp2oZTee1AZniXrg&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=activate the parasympathetic nervous system&f=false Chapter 5

Roediger, H. L. (2006). Bartlett, Frederic Charles. Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science. doi:10.1002/0470018860.s00665

Waxenbaum JA, Reddy V, Varacallo M. (2019) Anatomy, Autonomic Nervous System. StatPearls Publishing, from https://europepmc.org/article/nbk/nbk539845

Leave a Reply